With this quote I have the pleasure of introducing my home province (state) for this month’s 10,000 Bird’s Africa Beat. I live in a city called Pietermaritzburg, the capital of KwaZulu-Natal province. At 36,433 sq. mi (almost exactly the same size as Indiana), it is one of the smaller provinces of South Africa, but is the second most densely populated with over 10 million inhabitants. The bulk of the population (approximately 80%) belong to the Zulu tribe, but significant numbers of Xhosa and Afrikaans, as well as immigrants from India and Britain call this beautiful patch of land on Africa’s eastern seaboard their home.

The Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama was the first Westerner to make landfall in the province. This happened to be on Christmas Day 1497, hence the moniker “Natal”, the Portuguese word for “Christmas”. The land was of course already occupied by San (Bushmen) hunter-gatherers for millennia and more recently Bantu tribes of the Nguni branch (most notably Zulus and Xhosas). British settlers established a trading post at what was called Port Natal in 1824; it was subsequently renamed Durban and is now the province’s largest city and Africa’s busiest port. However, the interior remained untouched by settlers because of the ferocity of King Shaka and the Zulus. Matters changed in 1837 when Afrikaans Voortrekkers (also known as “Boers” meaning “farmers”) arrived in the province by oxwagon from the interior, via treacherous passes over the high Drakensberg Mountains, which form the western boundary of much of the province. Bloodshed was the inevitable result when these fiercely independent and tough settlers clashed with the mighty Zulus. At first the Zulu King Dingaan gained the upper hand by slaughtering a large contingent of Boers (including their leaders Piet Retief and Gert Maritz) but the infamous Battle of Blood River in 1838 lead to a division of the territory between what was later known as Natal to the south and Zululand to the north. The capital city of Pietermaritzburg was built after this formative battle and named in honor of the slain Boer leaders. The British Empire annexed Natal in 1843 and after the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, they also took occupation of Zululand. These combined territories became the province of Natal in 1910 and in 1994 it was renamed KwaZulu-Natal.

The ornithological history of the province is also interesting and a typical story of scientific discovery pioneered by brave explorers, naturalists and more recently, birders. Dr Andrew Smith was the first serious ornithologist and collector to visit KwaZulu-Natal. He was a Scottish army doctor and zoologist who came to the Cape in 1821 as surgeon to the Cape Mounted Rifle Corps. He arrived in Durban in 1832 on a political and exploratory expedition and interviewed King Dingaan. Dr Smith was later in charge of medical services in the Crimea but had a feud with Florence Nightingale and was severely criticized for mismanagement, yet despite this, he was knighted in 1859. In KwaZulu-Natal, he discovered, amongst many other birds, Natal Francolin, Red-capped Robin-chat (which was known as Natal Robin until recently), Swamp Nightjar (also known as Natal Nightjar), Mangrove Kingfisher and African Broadbill (the genus name Smithornis celebrates Dr Smith).

The famous Verreaux family made several expeditions into the province through the 1820’s and 1830’s, procuring specimens for rich collectors. After one 3 year stint, they left with 131,405 specimens, including birds, mammals, reptiles, plants and even human remains (which were only recently repatriated for burial in Africa!) They discovered Gurney’s Sugarbird during their time in South Africa.

Johan Wahlberg, a Swedish naturalist and collector, arrived in 1839 in the company of Frenchman Adulphe Delegorgue. Delegorgue’s main ornithological contribution was collecting Delegorgue’s Pigeon in the now vanished forests of Durban, but besides this, he had little significant input. However, he did publish a journal of his travels in the province, which makes for fascinating reading. Wahlberg travelled even more extensively and amassed a huge bird collection. In KwaZulu-Natal, he collected the type specimens of Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird, White-eared Barbet, Blue Swallow, Brown Scrub-Robin, Short-tailed Pipit and other species. In 1856, Wahlberg was killed by an Elephant near Lake Ngami in Botswana without ever publishing an account of his travels, but fellow Swede Carl Sundevall cataloged his collection at the Stockholm Museum and described the birds Wahlberg collected. Sundevall named Wahlberg’s Eagle and Wahlberg’s Honeyguide in his memory.

Thomas Ayres arrived in 1850 and farmed in Cowies Hill near Durban, as well as collecting birds for additional income. During much of the 19th century, it was fashionable for Victorian and European gentry to own a collection of birds and other curiosities and it was a lucrative practice to supply such specimens. Ayres discovered Orange Ground Thrush, Ayres’ Cisticola and Ashy Flycatcher in the process. In the 1870’s, much collecting was done by several officers of the British regiment in the province, most notable was Captain George Shelley. He was a nephew of the famous poet, Percy Shelley, and had Shelley’s Sunbird named after him.

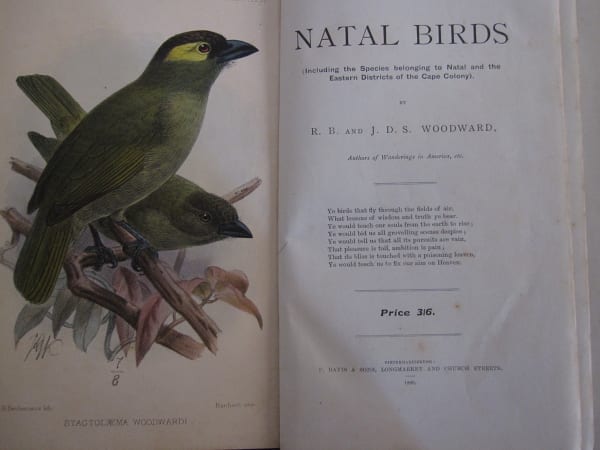

The Woodward brothers’ time was next. Reverend Robert and his brother, John, were Anglican missionaries in the province between 1881 and their deaths in 1905. In 1899 they published “Natal Birds”, from which the opening quote was taken. This was the first book on the birds of KwaZulu-Natal. Their explorations included two oxwagon journeys into Zululand where they explored Ngoye Forest and the Lebombo Mountains. They discovered Woodward’s Barbet and Woodward’s Batis, which were named in their honor by Captain Shelley.

Captain Claude Grant worked in the province from 1903-07. He discovered Rudd’s Lark at Wakkerstroom and in Southern Mozambique, he collected the first specimens of Rudd’s Apalis, Neergaard’s Sunbird and rediscovered Pink-throated Twinspot (which had been “missing” since the 1820’s when the Verreauxs erroneously claimed to have collected it in Cape Town.) The lark was named after Charles Rudd, a mining magnate and business partner of Cecil John Rhodes (together they founded De Beers Mining in Kimberly and Goldfields of SA in Witwatersrand, two of the world’s largest mining companies). Rudd was a keen ornithologist and financed Captain Grant’s expeditions which discovered the new birds. The sunbird was named in honor of Neergaard, a mining staff recruiting officer for Goldfields based in southern Mozambique who assisted Captain Grant during his expedition. Grant co-authored “Birds of the Southern Third of Africa” with Macworth-Praed in 1962.

Roden Symonds hailed from Pietermaritzburg but was based at Giants Castle in the Drakensberg Mountains for many years as a conservator. Besides San rock paintings, he took a number of collecting expeditions and has Drakensberg Siskin Serinus symonsi named after him. Durban museum based ornithologist Philip Clancey took numerous expeditions into Zululand and Mozambique, discovering several new subspecies as well as a new species to science, Lemon-breasted Canary, in 1961. Clancey was a prodigious publisher of papers and books, including “Birds of Natal and Zululand”, all lavishly illustrated with his excellent and distinctive bird paintings.

In more recent times, many other local ornithologists and birders have added to our knowledge of the province’s birds. Worthy of specific mention include Ian Sinclair – who discovered numerous new bird records in the province, chasing vagrants and becoming the first person to see 800 species in Southern Africa, something that had been considered far from possible. Digby Cyrus and Nigel Robson published the “Bird Atlas of Natal” in 1980, which mapped all bird sightings between 1970-1980. Gordon Bennett published “Where to see birds in Natal” and has been an active provincial birder for many years. Prof. Gordon Maclean was talented as both an ornithologist and a birder, he authored two editions of Robert’s Birds of Southern Africa and published numerous other books and papers. James Wakelin is a prime example of a modern ornithologist and conservator. He worked for Ezemvelo (the provincial parks authority) and was an avid bird bander who also worked on DNA analyses, radio tracking, monitoring endangered species nests etc. Hugh Chittenden is a master photographer and birder who has done many studies of local birds. He has published “Robert’s Fieldguide to Birds of Southern Africa”, “Top Birding Spots of Southern Africa”, and is busy with a new fieldguide to regional variations of Southern African birds. Hugh was recently awarded an honorary doctorate for his contribution to ornithology.

One way of measuring the growth of knowledge of KwaZulu-Natal’s birds is tallying up the species recorded through the years. In 1899, the Woodward brothers reported 383 species in their “Natal Birds”. This total includes several invalid species such as the ruddy and olive forms of Olive Bushshrike split as two species and the yellow-shouldered form of Black Cuckooshrike being listed as a Hartlaub’s Cuckooshrike. In 1964, Clancey’s “Birds of Natal and Zululand” raised the total to 590. By the end of the 1970-1980 bird atlas project, Cyrus & Robson added 56 new species, taking the provincial total to 646. With the advent of more birders, better optics, modern fieldguides and other information, the list now stands at over 710 species and additions are found every year. This is an incredible number of species for a subtropical region of its size and a visit to South Africa would not be complete without exploring the green province of KwaZulu-Natal.